The guest speaker at the September meeting of Keighley Astronomical society was Mr Roy Gunson from Mexborough & Swinton Astronomical Society.

His presentation started on a cold morning in 1857, in Dundee, Scotland, a girl was born who would one day light up the universe; not with a telescope, but with brilliance. Her name was Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming.

Mr Roy Gunson from the Mexborough and Swinton Astronomical society is welcomed to deliver his presentation by Dr Adrian Smith.

Mr Gunson of course has a great interest and knowledge of astronomy but he also takes great interest in the study of families, family history, and the tracing of lineages. ‘Genealogy’.

Williamina was born at 86 Nethergate, Dundee, on 15th 1857, to parents Robert Stevens, a carver and gilder, and Mary Walker. She was one of several children and as an older child she looked after her younger siblings. She had family members who had immigrated to the city of Boston, in the United States.

Fleming developed and implemented her own system for classifying stars based on the amount of hydrogen visible in their spectra. A stars with the most hydrogen was classified as Type A, the next most as Type B, and so on. This method allowed her to classify more than 10,000 stars for the first Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra in 1890.

She married James Orr Fleming, an accountant and widower of Isabella Barr, at Paradise Road, Dundee, on 26th May 26 1877. Mr Gunson speculated that checking birth certificates and census returns that Williamina was pregnant at the time of her marriage to James Fleming. Not long after her child was born the pair travelled to New York.

But life took an unexpected turn when she arrived in the United States. She was abandoned; left alone with her child in a foreign land. She made her way to Boston where she had relatives living there. Mr Gunson believes that Williamina had been in Boston on a previous occasion where she took a job as a housekeeper in the home of Edward Pickering, director of the Harvard College Observatory. Mr Gunson suggested that Edward Pickering was more than likely the father of her child.

She also established a method for comparing plates recorded at different times, which was crucial for discovering variable stars.

The story line later promoted by Harvard Collage clearly to cover up the circumstances of her pregnancy is that it was at this point she was working for Edward Pickering as the housemaid; and that Pickering became frustrated with his male assistants at the Harvard College Observatory. According to legend, he famously declared his maid could do a better job. In 1881, Pickering hired Fleming to do clerical work at the observatory.

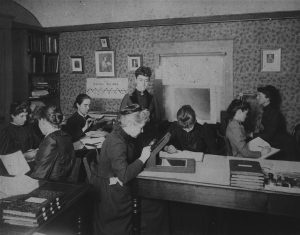

She stunned everyone, said Mr Gunson because with no formal scientific education, she began analysing photographs of the night sky with unmatched precision. She became the first of the Harvard Computers; a group of brilliant women behind some of astronomy’s greatest breakthroughs.

While there, she devised and helped implement a system of assigning stars a letter according to how much hydrogen could be observed in their spectra. Stars classified as A had the most hydrogen, B the next most, and so on.

The Harvard Computers: In 1881, Fleming became the first of the “Harvard Computers,” a team of women who analyzed the vast collection of photographic glass plates created by the observatory’s telescopes.

Later, Annie Jump Cannon would improve upon this work to develop a simpler classification system based on temperature. Fleming contributed to the cataloguing of stars that would be published as the Henry Draper Catalogue. In nine years, she catalogued more than 10,000 stars. During her work, she discovered 59 gaseous nebulae, over 310 variable stars, and 10 novae.

In 1907, she published a list of 222 variable stars she had discovered. In 1888, Fleming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on Harvard plate B2312, describing the bright nebula (later known as IC 434) as having “a semicircular indentation 5 minutes in diameter 30 minutes south of Zeta Orionis.” The brother of Edward Pickering, William Henry Pickering, who had taken the photograph, speculated that the spot was dark obscuring matter.

Horsehead Nebula: In 1888, she was the first to identify the Horsehead Nebula by recognizing its distinctive “semicircular indentation” on one of the photographic plates.

All subsequent articles and books seem to deny Fleming and W. H. Pickering credit, because the compiler of the first Index Catalogue, J. L. E. Dreyer, eliminated Fleming’s name from the list of objects then discovered by Harvard, attributing them all instead merely to “Pickering” (taken by most readers to mean E. C. Pickering, director of Harvard College Observatory).

By the release of the second Index Catalogue by Dreyer in 1908, Fleming and others at Harvard were famous enough to receive proper credit for later object discoveries, but not for IC 434 and the Horsehead Nebula, one of her early observations. Fleming was placed in charge of dozens of women hired to do mathematical classifications, and edited the observatory’s publications.

The Horsehead Nebula was discovered in 1888 by Williamina, who found it on a photographic plate at the Harvard College Observatory. The image was taken with the observatory’s 8-inch Draper telescope. The unique, dark shape of the nebula was captured on a plate used for the Henry Draper Catalogue, an ambitious project to survey and classify stellar spectra

In 1899, Fleming was given the title of Curator of Astronomical Photographs. In 1906, she was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the first American woman to be so elected. An historic achievement in a male-dominated field.

Soon after, she was appointed honorary fellow in astronomy of Wellesley College. Shortly before her death, the Astronomical Society of Mexico awarded her the Guadalupe Almendaro medal for her discovery of new stars. She published A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907) and Spectra and Photographic Magnitudes of Stars in Standard Regions (1911). She died in Boston of pneumonia in 1911.

Her work didn’t just study the stars. She became one said Mr Gunson

Williamina Fleming proved that greatness can come from the most unexpected places. That brilliance doesn’t need permission; and that a determined woman can change the very way we see the universe.

Her story continues to inspire dreamers and trailblazers to this day.